The Electoral College is Stupid, but so is National Popular Vote

Yeah, this is clickbait. But hear me out!

An election year is here again. And, given the political leanings of the vast majority of my friends, so is the trauma of the Electoral College. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by 2.845 million votes (2.1% of total turnout), but lost the Electoral College thanks largely to Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and my home state Michigan. The trauma is so deep that most of the people I know who voted in the Democratic primary didn’t vote for the candidate they agreed with the most or who had the best policy positions. Instead, they opted for the candidate they thought was most likely to win the general election in just the three states that tipped the election to Trump last time around.

Since 2016, the liberal parts of my social media echo chamber have been complaining endlessly about the Electoral College, and rightfully so. The fact that Democrats won the popular vote in 2016, but not the election, does feel rather undemocratic. But what I don’t understand is the proposed solution I see most often - the National Popular Vote Bill.

Essentially, the National Popular Vote Bill forces states to allocate all of their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote as opposed to their state’s popular vote 1. This would have resulted in a President Clinton instead of President Trump in 2016 and a President Gore instead of a President Bush in 2000. I get the appeal, but I don’t think it holds up to scrutiny.

First, I think it’s unlikely to ever get enough states on board that it will take effect. There are two major groups of states which would essentially be throwing away their power over federal policy by signing on:

- Rural states, like Wyoming, get a disproportionate number of votes in the Electoral College by design. A vote in Wyoming has a larger sway over the outcome of an election than New York.

- Swing states, like Michigan, have an even more disproportionate influence over the outcome of the election than rural states. Winning just a few of them, as we saw in 2016, is enough to win in the Electoral College regardless of the national popular vote. These states can use their electoral influence to get preferential treatment from political parties and candidates - why would they give that up?

As long as rural and swing states have 270 electoral votes between them, I don’t think the National Popular Vote Bill will get the 270 votes it needs to take effect. Pretty much by the definition of a “swing state”, this will always be the case.

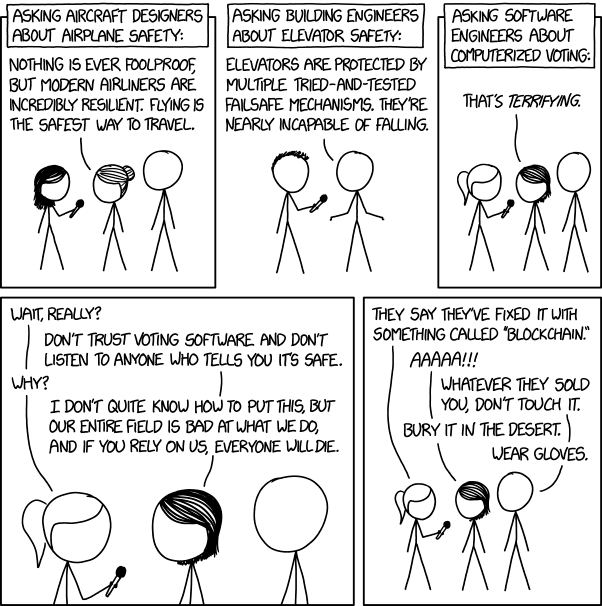

Second, I think it runs against the intent of the U.S. Constitution 2. Since the founding of the country, U.S. elections have been run independently from state to state. While it’s certainly open for debate whether this is a feature or a bug of the U.S. electoral system, I think it’s a feature because it makes our elections more robust. If one node in the election network goes down, we still have 49 others that should be fine. The National Popular Vote Bill undermines this by collapsing all state elections into one national election. In 2016, for example, any election mistake or interference that altered 3 million votes anywhere would have been enough for President Trump to win the election without the popular vote. Given the rather weak election security practices in many states, I don’t think this is very hard to imagine.

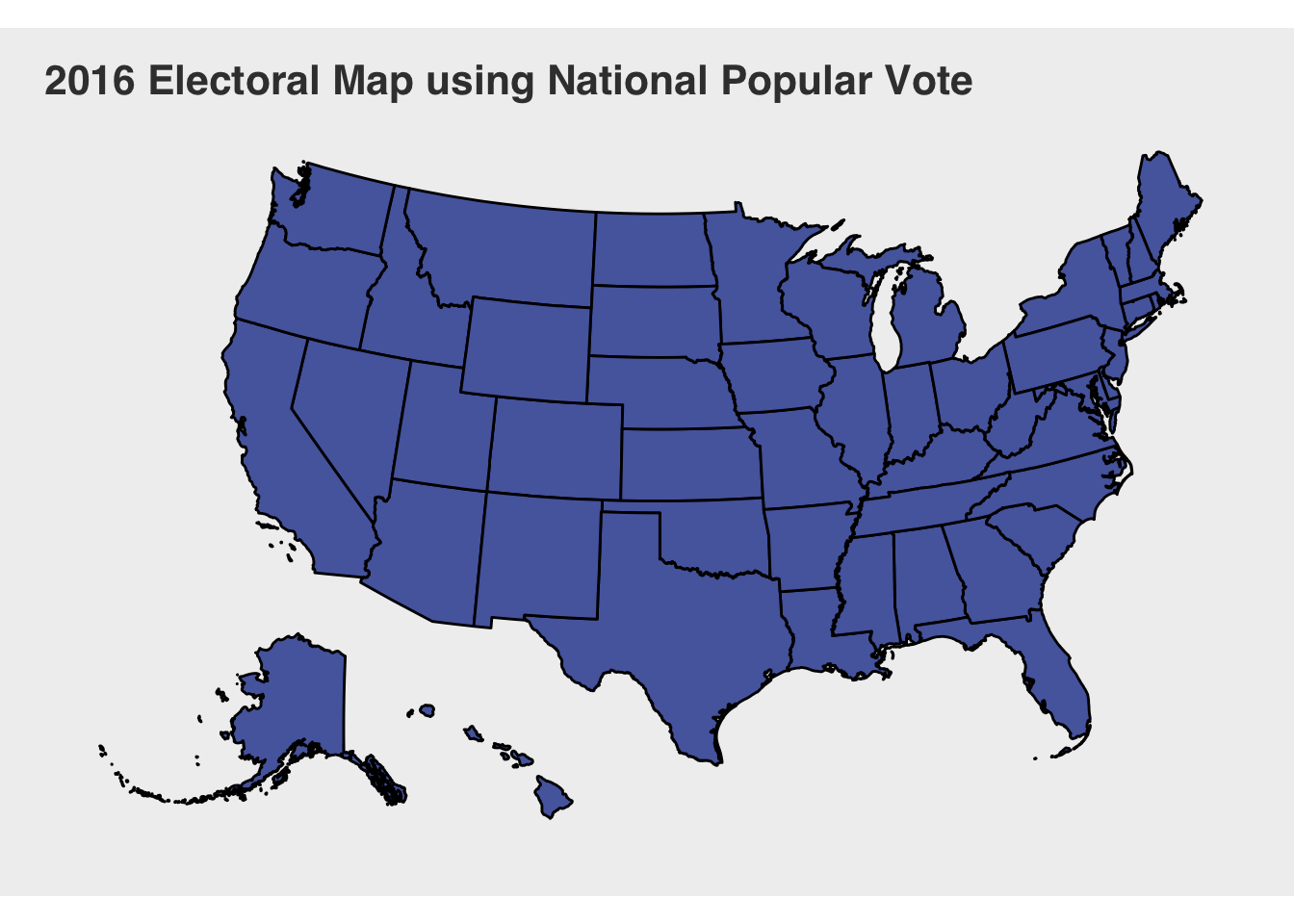

Third, I find the whole thing to be hardly more democratic than the Electoral College. The Electoral College set out to give all states an independent voice on who becomes the President, and the National Popular Vote Bill erodes that independence. Moreover, it still fails to accurately reflect the heterogeneity of the state-by-state vote. The map of a national popular vote election in 2016 doesn’t exactly look more democratic to me:

Finally, by automatically handing the presidential election to the popular vote winner, it practically guarantees that no third party will make a serious presidential run. Long term, I think this tends to make partisanship worse, as neither party has an incentive to appeal to more than half the country. And because there will never be a serious third party run, voters are incentivized not to vote for a the politician or party which best represents their beliefs, but rather the one that they’d rather not lose. This traps us in a political sort of Nash Equilibrium, where we’re stuck in a sub-optimal state which is stubbornly stable.

Rather than blame the Electoral College, or force all states to conform to the national popular vote, electoral reform should probably be a little more nuanced. I think the underlying problem is our assumption that electoral votes should be winner-take-all. It wasn’t always this way, and there’s nothing in the U.S. Constitution that mandates it. Rather, both political parties are perfectly well aware of how the electoral college entrenches power between the two of them and therefore are content to keep it that way.

Other Ways of Allocating Electoral Votes

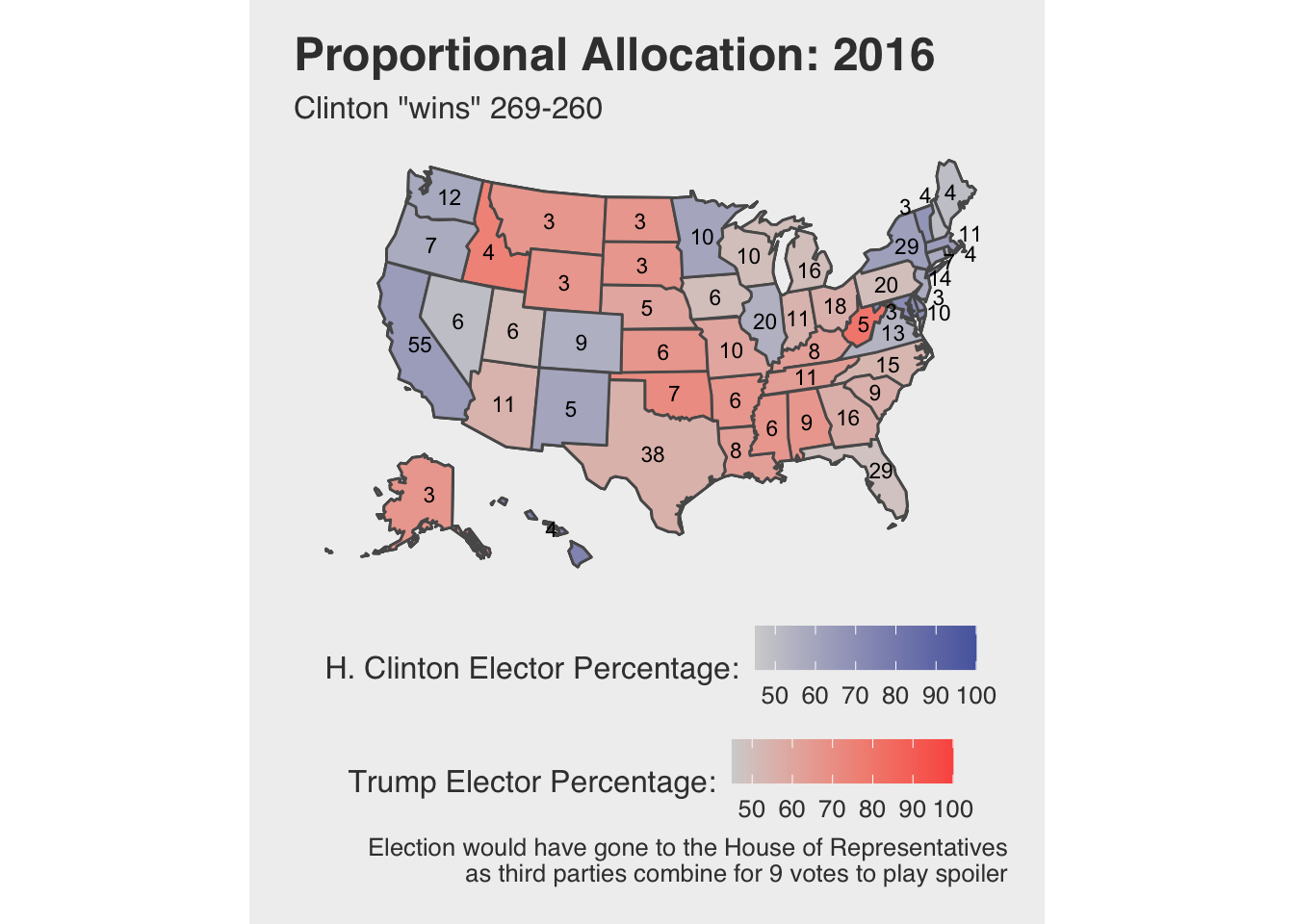

Rather than use a winner-take-all system, it makes more sense to allocate electoral votes proportionally, matching the popular vote. For example, Michigan in 2016 would have allotted 9 of 16 electoral votes to President Trump and the other 7 to Hillary Clinton. This is how most Democratic primaries are run, after all. What would that look like?

Allocating a discrete number of electoral votes based on vote share, a continuous variable, is actually more interesting and nuanced than it first seems. For example, consider a hypothetical state that has 11 electoral votes, split between a Republican candidate, a Democratic candidate, and a third-party candidate. In this system, it’s much more plausible the third party candidate gets a significant share of the votes. Consider the results in the following table:

| Candidate | Vote Share | Electoral Votes |

|---|---|---|

| Republican | 48% | 5.28 |

| Democrat | 40% | 4.4 |

| Third-Party | 12% | 1.32 |

In proportional allocation, 48% of 11 votes rounds to 5 votes for the Republican, 40% rounds to 4 votes for the Democrat, and 12% rounds to 1 vote for the third party candidate. This only adds up to 10 total though, so we have one more vote to allocate.

We could avoid this issue by always rounding up, so that the Republican candidate rounds up to 6 votes and the Democrat to 5 votes, but that isn’t exactly fair - the third-party candidate doesn’t get the one vote they deserve because the 11 votes are spent by the time we get to allocating their votes.

The obvious solution is to round to the nearest delegate, and then if there are some left over afterward, go through each candidate again and allocate the remaining votes by rounding up. This results in the Republican getting 6 votes, the Democrat getting 4 votes, and the third-party candidate getting 1 vote. While this is the most fair, it does demonstrate a behaviour of the Electoral College you can’t get around - allocating a relatively small integer number of Electoral Votes based on the vote share leads to oddities. A popular/electoral vote split is possible, no matter how you allocate votes, just based on integer rounding.

Another interesting artifact of proportional allocation is that it establishes a very clear minimum vote share required to qualify for an electoral vote,. This is similar to the Democratic primary, which has a 15% threshold. In this case, the threshold is 1/2*N, where N is the number of electoral votes for that state. In a small state with three electoral votes, a candidate needs to get 1/6th (roughly 17%) of the vote. But in a state like California, with 55 votes, a candidate only needs to get 1/110th (roughly 0.9%) of the vote to qualify.

Even with proportional allocation, smaller states still have a disproportionate number of votes. Because of the lower floor needed to win delegates in populous states, it could give an even wider advantage to the candidate that wins small states, because it’s harder for the loser to get electoral votes in small states than large ones. It’s also likely a field of battleground states will still emerge as campaigns do the math on the percentage of the vote they need to shift to get the maximum number of votes possible. The battleground will be wider, but there are still states that candidates would waste time to visit. For example, Democrats in 2020 would have no real reason to visit the 3-vote states in the West (Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas) because any vote share between 16.7% and 50% will get them one electoral vote.

Nonetheless, allocating electoral votes proportionally does make the electoral college more representative. But it also makes it less likely that a major party candidate gets a majority of the electoral votes. For example, Bill Clinton won 69% (370) of the electoral votes in 1992 despite only getting 43% of the popular vote. In proportional allocation, he would have only gotten 234 electoral votes, and failed to clear the 270 needed to win. Ross Perot would have played spoiler, with 99 electoral votes, and the election would have gone to the House of Representatives. This demonstrates the increased viability of third party candidates in a proportional system.

Unfortunately, that means some kind of Proportional Allocation Vote Bill would probably run into the same fate as the National Popular Vote Bill. Because both major political parties are better off without third parties, they’re never going to change the Electoral College to a system that makes them more viable.

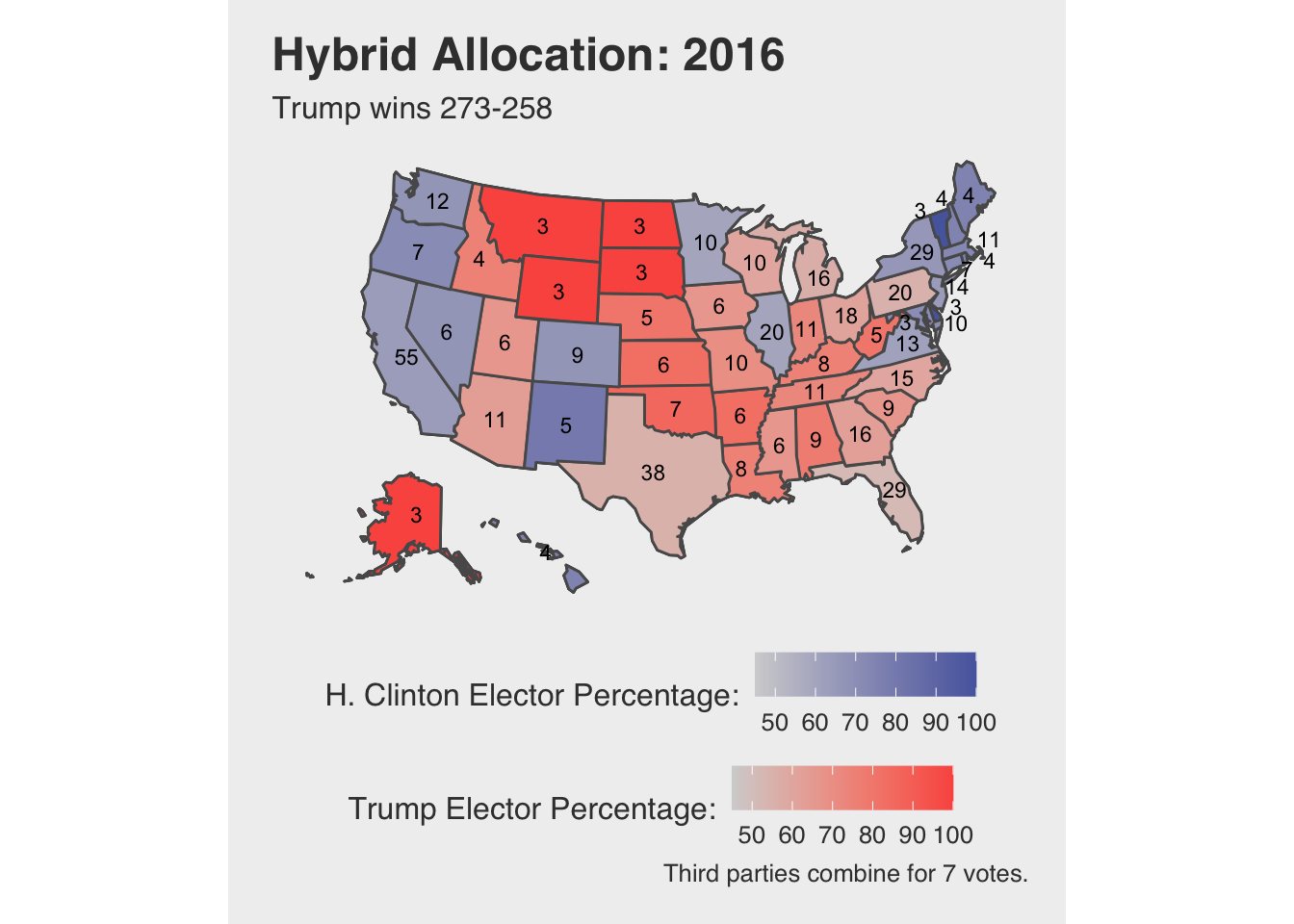

But I think there’s a compromise that would make the Electoral College more representative, give third parties more of a chance, but still have a strong enough institutional bias toward the two major parties that they’d perhaps be willing to consider it. I call it Hybrid Allocation.

The number of electoral votes each state gets is equal to the number of seats they have in Congress. That’s 2 for every state from the Senate, plus their number of seats in the House of Representatives. Senate seats are always statewide, so why not make the 2 electoral votes from the Senate be winner-take-all, and allocate the electoral votes from the House of Representatives proportionally 3? This decreases the number of electoral votes effectively in play for third-party candidates by 2 in each state 4, therefore also increasing the vote share required to qualify for electoral votes. It also skews the electoral votes more in the favour of the state’s popular vote winner, which is almost always going to be a major party candidate.

But compared to winner-take-all, it still increases the electoral battleground beyond the half dozen or so swing states, makes third parties more viable than they are now, and makes the Electoral College more closely represent both the national popular vote and the geographic distribution of the vote. It still has a bitter aftertaste, but I think it’s probably the best we can do without overhauling the Constitution or asking political parties to show an altruism which is counter to their foundational character.

What does this look like?

In order to see the effect these electoral vote allocation schemes could have on elections, I created a shiny app that runs alternative history elections from 1976 to 2016 under each voting scheme. While these aren’t perfect representations of what the true maps may have been under Proportional and Hybrid allocation because vote behaviour probably would be different than it was under winner-take-all allocation. That said, I do think it gives us a good sense for how elections may have played out differently under different allocation systems and supports the argument I was making earlier.

As an added bonus, I hooked the shiny app into fivethirtyeight’s forecast so that we can see what the 2020 election could look like under the various allocation schemes as well.

What do you think? You can let me know via email, or you can always hit me up on twitter!

Footnotes

It’s worth noting that the bill only becomes “live” when the states that sign on have at least 270 combined electoral votes. Right now, they only add up 196. So the same old electoral college is what we get in 2020.↩︎

More specifically, I don’t think the Founders would support the National Popular Vote Bill. But that doesn’t mean I think it’s unconstitutional. After all, the Constitution doesn’t say anything about how states should allocate their electoral votes.↩︎

We could just give one electoral vote to each congressional district and 2 votes to the statewide popular vote winner. However, given the large structural advantage in congressional districts parties can give themselves through gerrymandering, I don’t think that’s a good idea.↩︎

The one quirk of this system is that it does make states with only 3 electoral votes (2 from the Senate and 1 from the House) effectively winner-take-all, like they are now.↩︎